|

Transition

and the Sublime Lecture

by Johnes Ruta, independent curator & art theorist

|

||||||

|

All

Photo Credits: "Art Across Time" Third Edition

- by Laurie Schneider Adams

(McGraw-Hill, 2007, ISBN: 0072965258) |

||||||

| For

a better understanding of the transition from medieval and Byzantine

styles of art into the "Renaissance," I'd like to briefly

trace the forces that allowed Greek and Roman art to survive the Dark

Ages and to gradually emerge into the historical developments that

brought about a new age of expression in music, art, philosophy, the

rebirth of culture that was called "The Renaissance." If

we have any idea of the thousand years between 500 AD and 1500 AD,

we must acknowledge that after the collapse of the Roman Empire in

the 6th century, the Christian Church started out as the preserver

of the literacy and the vast knowledge that existed in ancient Greece

and the Roman Empire. For the first several hundred years of this

1000 years, barbarians stalked the countryside so that trade between

towns always came under attack by brigands. This was the beginning

and cause of the Age of Chivalry, when knights ventured forth to rid

the roads of these brigands.

But for the Church, there were no other places of education in the Western world, but by the late 10 hundreds, the leadership of the Church had decided that its momentum of social power determined it was now time to reclaim the now Islamic "Holy Lands." The First Crusade was launched, and the kings of Europe were commanded to supply armies for this purpose. By this time, the somewhat tribal farming communities of Western Europe had come under the dominance and so-called "protection" of the aristocracies of the Noble class, especially in the Holy Roman Empire in Germany and Austria, and the Norman Conquest of the Saxons in England. The Church monasteries continued as the centers of learning even as the first universities were established, and as the centers of the preservation and publication of ancient writings carefully copied and beautifully illustrated into Illuminated Manuscripts. These themselves are a wealth of knowledge. |

||||||

|

||||||

|

Unfortunately, from 1050 for the next 800 years, the Church also narrowed the tradition of ancient knowledge to mesh only with the tenets of faith and religious doctrine as established back during the Roman Empire when Christian dogma replaced paganism as the state religion. The categorizations of knowledge given in the works of Aristotle became the defined standard of all forms of nature, form, reason, and logic in the Western and Near Eastern worlds. The

Church served as an important buffer between the peasant and serf

classes against their frequent abuses by the aristocracy which lavished

itself in wealth as extracted from the peasantry. Now expressions

of personal mysticism outside the clergy became strictly forbidden

and branded as heresy, enforced by the Holy Inquisition, and artistic

expression was regulated by accepted traditional styles. Minor artists

worked within the nearly anonymous confines of the guilds; and successful,

individually commissioned artists needed In this survey of the "Early Renaissance" we must first realize that there were "2 TRAINS RUNNNING" -- the one in the south, first built by Arab Optical scientists in the 10th century and engineered in Italy by GIOTTO in the early 1300s-- and that in northern Europe, first built by Charlemagne in the 9th century and setting off in 1404 on a path from Bruxelles carrying the funeral cortege of Phillip the Bold back to Burgundy. |

||||||

| I.

After the Fall of In the late Roman Empire, the system of education had been devised by Martanius Capella in the fifth century, based on study of the the Seven Liberal Arts which consisted of two categories of study - the Trivium of three subjects: 1. Grammar 2. Dialectic [intellectual debate] 3. Rhetoric,

Quadrivium of four subjects: The philosopher Boethius, the author of "Consolations of Philosophy," also promoted this system.

The Dark Ages were a period of hardship and danger.

The only system of education to continue was now based in the fortified

monasteries, where scribes were trained to copy surviving Greek

and Roman texts in order to preserve them for posterity. |

||||||

|

||||||

|

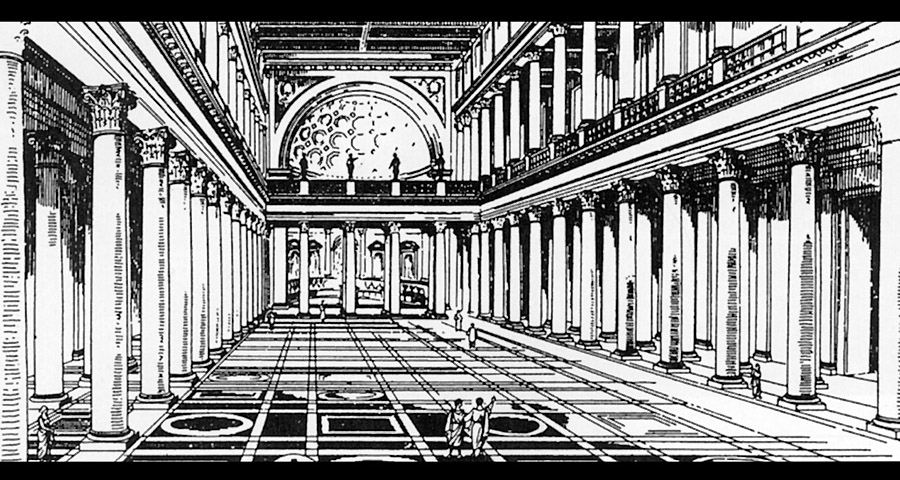

The Baths of Caracalie, Rome.

Enormous Corinthian columns support the groin vaults in the ceiling of the central hall. 952 baths. Restoration drawing. (Photo: Art Across Time 7.15) |

||||||

| II. The Court of Charlemagne, AD 742-814 | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| III.

Illuminated Manuscript production |

||||||

| Produced

all through the Dark Ages from AD 400 to 1600.

Various Bestiaries

showing zoological studies and allegories, |

||||||

| IV. Cathedral building | ||||||

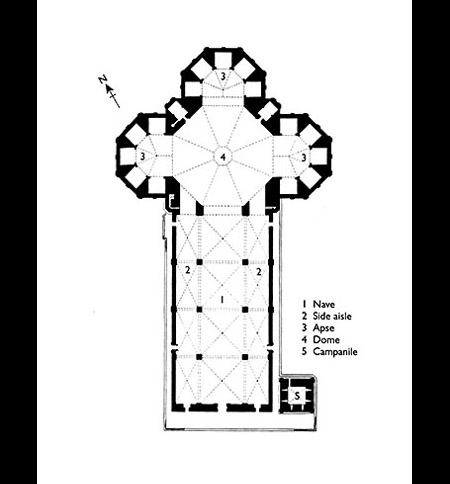

| Romanesque

construction style, begun in the early reign of Charlemagne. The term "Romanesque" began as a derogatory to describe the "debased" form of the architecture of ancient Roman basilicas. From 1100 these creations proceed into façade and entryway sculpture figures of intricate design. The floor-plan of these cathedrals was in the shape of the Cross with the long Nave and the Choir section behind the altar crossed by transept wings. Stone vaults above eventually replaced the use of wood timber ceilings - too heavy to balance lasting constructions. The stone vaults, with columns and forward protruding vertical pilaster columns, also gave an excellent dispersion of sound for the Gregorian Chants continually sung by monks. Cathedral

height became a matter of great rivalry, especially in France :

|

||||||

| V. Education systems in the Middle Ages | ||||||

| The

first higher education institution in medieval Europe was the University

of Constantinople, followed by the University of Salerno (9th century),

the Preslav Literary School and Ohrid Literary School in the Bulgarian

Empire (9th century). The first degree-granting universities in Europe were the University of Bologna (1088), the University of Paris (c. 1150, later associated with the Sorbonne), the University of Oxford (1167), the University of Cambridge (1209), the University of Salamanca (1218), the University of Montpellier (1220), the University of Padua (1222), the University of Naples Federico II (1224), the University of Toulouse (1229, the University of Orleans (1235); the University of Siena (1240); the University of Coimbra (1288). Some scholars argue that these medieval universities were influenced in many ways by the medieval Madrasah institutions in Islamic Spain, the Emirate of Sicily, and the Middle East (during the Crusades). The earliest universities in Western Europe were developed under the aegis of the Catholic Church, usually as cathedral schools or by papal bull as studia generali (n.b. The development of cathedral schools into universities actually appears to be quite rare, with the University of Paris being an exception - see Leff, Paris and Oxford Universities), later they were also founded by Kings (Charles University in Prague, Jagiellonian University in Krakow) or municipal administrations (University of Cologne, University of Erfurt). In the early medieval period, most new universities were founded from pre-existing schools, usually when these schools were deemed to have become primarily sites of higher education. Many historians state that universities and cathedral schools were a continuation of the interest in learning promoted by monasteries. In Europe, young men proceeded to university when they had completed their study of the trivium-the preparatory arts of grammar, rhetoric and dialectic or logic-and the quadrivium: arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy. |

||||||

The term "schola" derives from ancient Greek for "leisure" -- as it was recognized since antiquity that one must possess leisure time in order to contemplate the ultimate nature of things - leisure is an essential condition. In the middle ages, no clear distinction was made between philosophy and theology - Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) suggested that philosophy operated on premises supplied by nature, and theology operated on premises supplied by revelation. Aquinas succeeded in re-establishing the acceptability of Aristotle's philosophy, which at that time was under suspicion by more conservative Church theologians as pagan. The surviving texts came through the Muslim world and were translations from Arabic sources and commentaries. Aquinas' system of metaphysics perceived that matter in the universe was manifested in two ways: first as esse naturale, that is, the Form from Nature that makes a piece of matter the thing that it is; second, esse intelligible, is that which arises as an idea in a person's mind. Thomas Aquinas: "Beautiful things are those which please when seen, because they are felt to be rays from God's mind." The Byzantine

Empire was the eastern remnant of the Roman Empire which had also

divided the Church in the Great Schism |

||||||

|

The History of OPTICS

|

||||||

| Glossary * extromissive vision : sight occurs by the emission of light out of the eye, illuminating * intromissive vision : sight occurs by the entry of light rays into the eye. Light is believed to originate from the external world. |

||||||

| ANCIENT In optics, the Atomists promoted the Euclid Aristotle (384-322 BC) -- (intromissive principle) “Objects modify the intervening |

||||||

| HELLENIC Claudius Ptolemy (90 – 168 C.E.) (extromissive vision) Sight believed to be rays of light http://www.bookrags.com/biography/ibn-al-haitham-al-hazan-wop/ Documents regarding Al Hazan: The sun's rays proceed from the sun along straight lines and are reflected from every polished object at equal angles, i.e. the reflected ray subtends, together with the line tangential to the polished object which is in the plane of the reflected ray, two equal angles. Hence it follows that the ray reflected from the spherical surface, together with the circumference of the circle which is in the plane of the ray, subtends two equal angles. From this it also follows that the reflected ray, together with the diameter of the circle, subtends two equal angles. And every ray which is reflected from a polished object to a point produces a certain heating at that point, so that if numerous rays are collected at one point, the heating at that point is multiplied: and if the number of rays increases, the effect of the heat increases accordingly. Opticae Thesaurus Translated into Latin in 1270, Opticae Thesaurus was the first real contribution to the science of optics in the first millennium and had a great influence on both Bacon and Kepler. Many experiments were conducted in a dark room lit through a solitary hole. Outside the room, adjacent to the wall with the hole, Alhazen hung five lamps. He observed that these produced five 'lights' on the wall inside his dark room and that by placing an obstruction between one of the lanterns and the hole one of the 'lights' on the wall disappears. His observation that the lantern, the obstruction and the hole were in a straight line demonstrated that light travels in straight lines. ABU ALI HASAN IBN AL-HAITHAM (ALHAZEN) (965 - 1040 AD) Al-Haitham, known in the West as Alhazen, is considered as the father of modern optics. Ibn al-Haitham was born in 965 C.E. in Basrah (present (source: http://home.att.net/~mleary/alhazen.htm) |

||||||

| In the medieval centuries between the collapse of the Roman Empire and the beginning of universities in the 12th and 13th centuries, Europe had very few schools for children and illiteracy was wide-spread. Similar to modern "Liberal Theology" in Latin America, the medieval Church was the only real force standing between the aristocracy and the peasantry -- against the excesses of feudalism and the ill treatments of serfdom. In this situation, painting was considered a means to visually illustrate religious themes, and thereby to provide Hope to the people of a better world to come. However, from the beginning of the Holy Inquisition in 1184, shortly before the beginning of the Third Crusade in 1187, the Church demanded strict adherence to its tenets of dogma of principles of Faith and Creed. Personal mystical experience was suspect as heresy, and lay theoretical theology was also forbidden. |

||||||

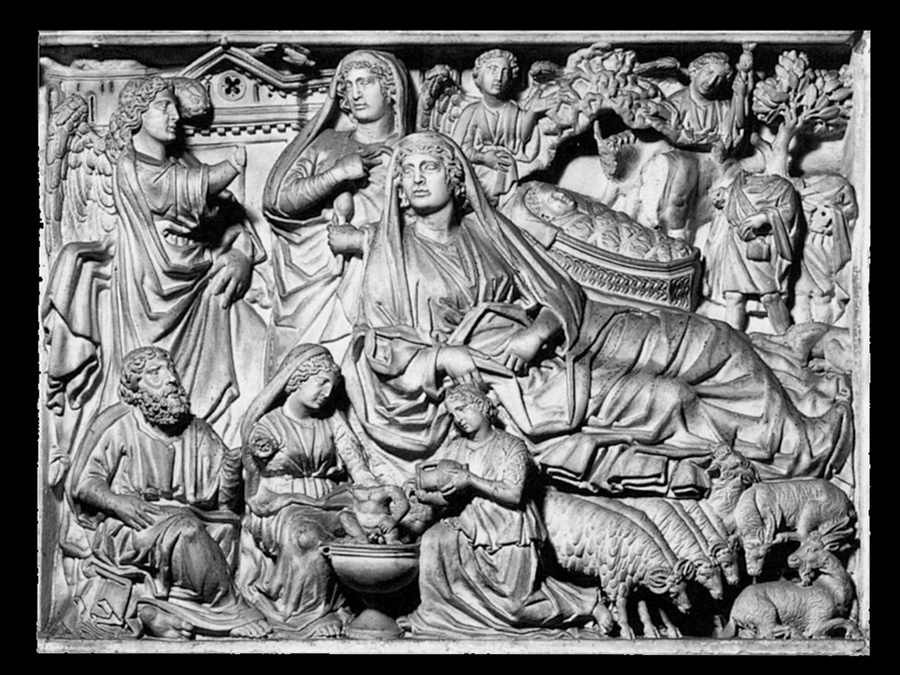

The Pisanos created

the Pulpit - Baptistry at Pisa (Nicola 1260). Used antique art as

a model for his art, attempted to create a Christian art style with

the realism and dignity of Late Roman art. The Holy Roman Emperor

Frederick II (d. 1250) was engaged in a deliberate revival of Roman

grandeur. Against the pure Byzantine style (flat gilded backgrounds)

there is the beginning of landscape backgrounds, possibly influenced

by the French Gothic style, where the artists might have visited.

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

Nicola

Pisano - Marble relief - Pisa

Chapel, 1260

upper left -"The Annunciation" ; center "The Nativity"; upper right "Annunciation to the Shepherds" . (Photo: Art Across Time12.2) |

||||||

| DUCCIO di Buoninsegna (c.1255-c1319)

The first great Sienese painter. Worked and retained the austere Byzantine style in use for centuries in Italy in which the backgrounds gilded and 2-dimensional. Considered a profound

innovator in his Solidity of forms. Used varied and elegant outlines

as the surface patterns and to describe forms. His early figures

have a doll-like quality, but his developing use of rich and subtle

color then enabled him to begin to portray the emotional depth |

||||||

|

||||||

|

Duccio

di Buoninsegna “Kiss of Judas”

1308

|

||||||

| GIOTTO di Bondone (c.1266/7

– 1337) Adaptation of Perspective from Arabic principles of sight. Influenced by sculpture style of Giovanni Pisano. Both born in “In the Ptolemaic world-picture,” says Titus Burkhardt, “the wider the heavenly sphere in which a star moves, the purer it is, the less conditioned, and the nearer the divine origin is the degree of existence and the level of consciousness to which it corresponds.” 9 On the walls of the Arena chapel in Padua, Giotto's great fresco The Last Judgment, consecrated in 1305, would manifest the incipient use of the principle of perspective in the con-vergence into a vortex at the bottom, the implied lines aligned to the edges of galleries of saints on either side of the throne of God overlooking the panorama of the Kingdom of Heaven. Thus the placement of background forms would be employed to construct the optical illusion of a 3-dimensional field. Upon the utmost verge of a high bank, By craggy rocks environ'd round, we came. Where woes beneath, more cruel yet, we stow'd. And here, to shun the horrible excess Of fetid exhalation upward cast From the profound abyss... (Inferno, Canto XI, 1-6) With Dante’s literary description and Giotto’s examples of implied convergence lines depicting recessive ceilings, Giotto’s artistic successors such as Taddeo Gaddi, Simone Martini, and the Lorenzettis, combined with principles found in the reappearance of the text of Euclid's Optics would eventually bring a recognition of convergence into the conscious principle of the “vanishing point” in the Perspective drawings of such Renaissance architects as Brunelleschi and Alberti in the early 15th century, thus disseminating the concept to their students Masaccio, Donatello, Paolo Uccello, and Piero della Francesca. |

||||||

|

||||||

|

Giotto

di Bondone “Kiss of Judas”

1305

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

Giotto

di Bondone “The Last Judgement”

fresco, Arena Chapel, Padua 1305

|

||||||

| Ambroglio LORENZETTI (active

1320-1345) Sienese painters Lorenzo and Pietro Lorenzetti extended the style of Duccio's concepts rendering solidity of form and emotional depth. Ambroglio's mural painting reflected the humanist interest in the republican form of government of their time - the shift away from the dominance of the aristocracy toward the influence of the merchant classes. This is the first panoramic representation in modern Western art. People freely move about the city in their activities and trades (a school, a cobbler shop, a tavern, merchant caravans, farmers working the fields) and their leisure (people riding horseback, men playing dice, ladies dancing). Ambroglio further developed the dimension of perspective and depth of field in detailed foregrounds and backgrounds. (Sadly, none

of the Lorenzetti family seems to have survived the Black Plague

of 1348.) |

||||||

|

||||||

|

Ambroglio

Lorenzetti “The Effects of Good Government in the City and

Conntry”

46 ft wide fresco, 1338-39, Sala della Pace, Palazzo Pubblico, Siena (Photo: Art Across Time 12.20a) |

||||||

|

||||||

|

Ambroglio

Lorenzetti “The Effects of Bad Government in the City”

46 ft wide fresco, 1338-39, Sala della Pace, Palazzo Pubblico, Siena (Photo: Art Across Time 12.20b) |

||||||

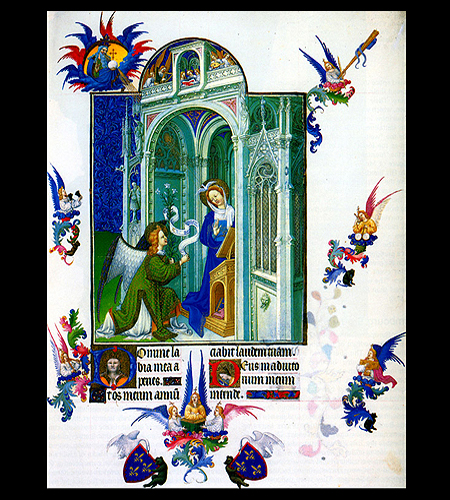

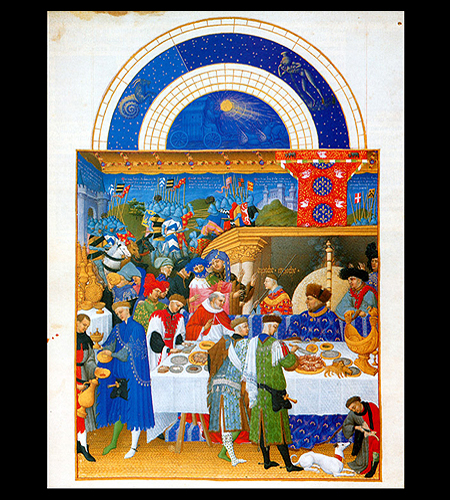

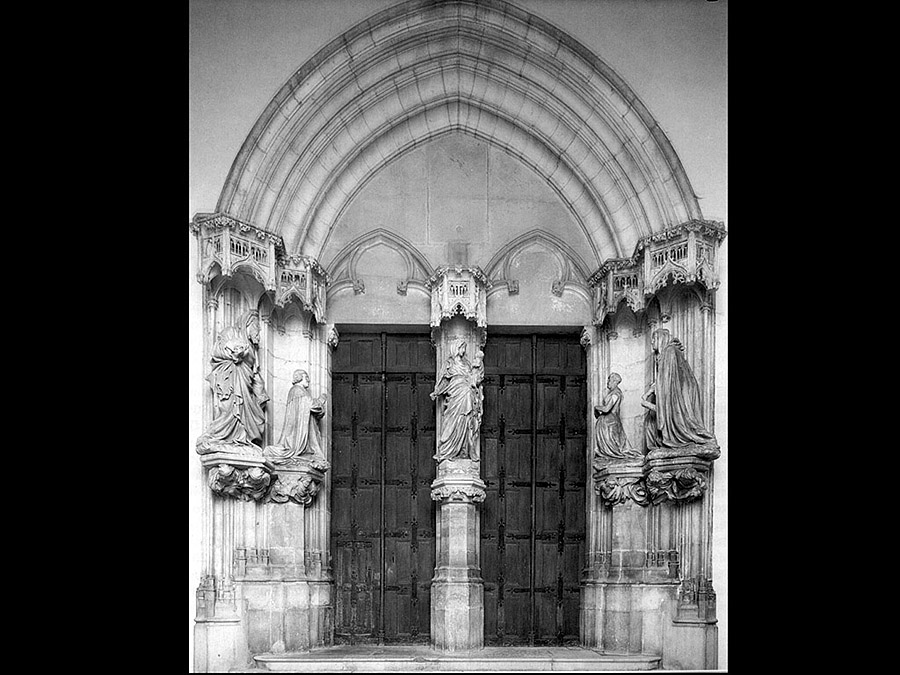

| ART

IN THE NORTH COUNTRIES - THE PARALLEL RENAISSANCE

The Burgundian Court, AD 1300-1450 The Limbourg

Brothers 12.29

Limbourg Brothers "Annunciation" 1413-1416 Claus Sluter (active 1379-1406) During the period of suffering and continual upheaval of the Hundred Years War, Claus Sluter, the Court sculptor of Phillip the Bold, the Duke of Burgundy, departed from the doll-like figures of previous style, and introduced a new representation of sensitive facial expression in sculptures both in the portal of the Chartreuse de Champmol" in Dijon, France, which reveal deeper physical and psychological characteristics in the figures, such as the "Virgin Mary and Christ" 1385-1393, and the "Well of Moses," a hexagonal pedestal with the statues of the prophets begun 1395, displayed an intense realism never seen before in European sculpture. Before its

destruction during the French Revolution, a crucifixion circle stood

above the center. Now the only surviving piece of that damage, the

head of Christ itself, displays in its face a mood of both intense

suffering and a profound release at His moment of death. This development

of style manifests a new feeling which is also evolving in the Humanist

philosophy of the 14th century such as Dante, whose "Divine

Comedy" told the lives of diverse individuals, then to Meister

Eckhart, a NeoPlatonist who considered metaphysics and spiritual

psychology in his widely published writings in the early 14th century,

and Petrarch, who recognized and defined the experience of the Dark

Ages in human history. Both Eckhart and Petrarch discovered and

published previously unknown philosophical writings from ancient

Roman, such as Cicero and Virgil. |

||||||

|

||||||

|

Claus

Sluter -- Portal of the Chartreuse de Champmol in Dijon, France

(Photo: Art Across Time 12.26) |

||||||

|

||||||

|

Claus

Sluter -- "Virgin Mary and Christ"

Portal of the Chartreuse de Champmol in Dijon, France (Photo: Art Across Time 12.27) |

||||||

|

||||||

|

Claus

Sluter -- "Well of Moses"

Chartreuse de Champmol in Dijon, France 1. David 2. Moses 3. Jeremiah 4. Zachariah 5. Isaiah 6. Daniel (Photo: Art Across Time 12.28) |

||||||

|

Robert Campin (1378-1444) |

||||||

|

||||||

|

Robert

Campin “Mercade Altarpiece” 1425-30 tempera

& oil on wood (Cloisters, NYC)

(Photo: Art Across Time 13.60) |

||||||

| Jan van Eyck (1399-1440) 1.10 “Virgin in a Church” After working for Count John of The Arnolfi

wedding Portrait is the best known wedding painting in Western art.

It carries an array and depth of symbolism, starting with the comparative

height of the characters, man taller, standing upright, left hand

taking her right hand, his right hand held up in a ambiguous poise

of upright morality or stand-off-ishness. Arnolfi was both a money-lender

and an art dealer. The bride bows her head and gives her open right

hand in a posture of submission. Her left hand lays upon her fecund,

or pregnant belly. The marriage bed awaits in the background, with

light entering from the open window at left, drapery hanging over

above at right. The dog, symbol of both lust and loyalty gazes at

the viewer. |

||||||

|

||||||

|

Jan

van Eyck “Ghent Altarpiece” 1434, oil on wood, 14"w x 11" h,

Cathedral of Saint Bevon, Ghent, Belgium (Photo: Art Across Time 13.62) |

||||||

|

||||||

|

Jan

van Eyck “Ghent Altarpiece” detail

(Photo: Art Across Time 13.63) |

||||||

|

||||||

|

Jan

van Eyck “The Arnolfi Wedding Portrait” 1434, oil on wood, 21"w x 32" h, National

Gallery, London

(Photo: Art Across Time 13.67) |

||||||

|

||||||

|

Jan

van Eyck “The Arnolfi Wedding Portrait” detail

|

||||||

|

ROGIER van der Weyden (1399-1464) |

||||||

|

||||||

|

Rogier

van der Weyden “St.

Luke Depicting the Virgin"

Boston Fine Arts Museum (Photo: Art Across Time 13.70) |

||||||

|

Principles of panoramic landscape -- influence on Italian painting In European Courts of the nobility in the 15th century, the strong success of German and Netherlanish painting, with its style characteristics, such as detailed landscape depth of field and individualized moods in human faces, led by the 1460s to a very strong export art market of northern painting, especially to Naples and Florence. Works by many Northern painters, such as Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, Hugo van der Goes, Hans Memling, were also seen by Italian painters, amplified their departure from the flat Byzantine style, into the already developing display of landscape (what we would call) depth of field. Rogier van der Weyden made a pilgrimage in 1450 to Italy, visiting Rome, Florence, and Ferrara. He was commissioned by nobles such as Alessandro Sforza (1409-1479), and merchant families such as Battista Agnelli of Pisa, to paint or reproduce such paintings as St. Luke depicting the Virgin, The Deposition of Christ, The Entombment of Christ for Italian patrons. |

||||||

| Albrecht

Durer (1450-1516) Beginning in 1490 Durer travelled widely for study, including trips to Italy in 1494 and 1505-7 and to Antwerp and the Low Countries in 1520-1. During his visit to Venice on his second Italian trip Durer was especially influenced by Giovanni Bellini and Bellini's brother-in-law Andrea Mantegna, each then near the end of his career. In The Uffizi: A Guide to the Gallery (Venice: Edizione Storti, 1980, p. 57) Umberto Fortis comments that Durer's journeys enabled him "to fuse the Gothic traditions of the North with the achievements in perspective, volumetric and plastic handling of forms, and color of the Italians in an original synthesis which was to have great influence with the Italian Mannerists." |

||||||

| Hieronymus

Bosch (c.1450-1516)

16.3 “The Garden of Earthly Delights” |

||||||

|

||||||

|

Hieronymous

Bosch “Garden

of Earthly Delights"

Museo del Prado, Madrid (Photo: Art Across Time 16.3) |

||||||

| Matthias

Grunewald (1470-1528) 16.15 “Annunciation Virgin and Child” The Isenheim Altarpeice |

||||||

| Pieter

Bruegel the Elder (1525/30-1569)

16.6 “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus” |

||||||

|

Italian Renaissance,

AD 1400-1550 |

||||||

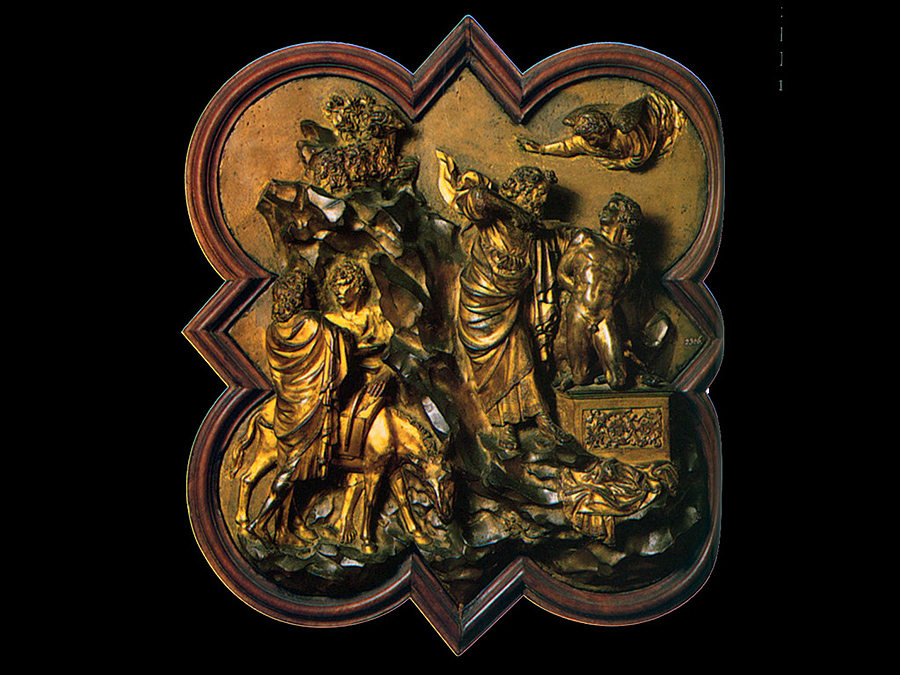

| Filippo

Brunelleschi (1377-1446) and Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378-1455) |

||||||

|

Ghiberti was

the most talented and respected sculptor in Florence. He was selected

to make two of the three bronze doors for the Baptistery in Florence

in 1404. The Baptistery construction was begun in 1059, and the

building completed in 1128, built in the Romanesque architectural

style. The competition for the Baptistery Doors was announced in 1401; the subject was the sacrifice of Isaac, and Ghiberti and Brunelleschi were the final contestants for the commission. Brunelleschi's entry possessed a greater sense of drama and violence, with the angel Gabriel seizing the arm of Abraham to stop him in the last instant before his is about to plunge the knife, having demonstrated his faith to God. But his piece was not as well constructed, with several pieces bolted to the bronze base. So Ghiberti won the competition, with his far more accomplished designs blending Gothic grace with the elegance of the nude figure of Isaac modeled on Classical sculpture, and the perfected one-piece construction of his piece.

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

Filippo

Brunelleschi design for the Baptistery Door competition "The

Sacrifices of Isaac" bronze

(Photo: Art Across Time 13.02) |

||||||

|

||||||

|

Lorenzo

Ghiberti's design for the Baptistery Door competition "The

Sacrifices of Isaac" bronze

(Photo: Art Across Time 13.03) |

||||||

|

Aware of the advanced expertise of Ghiberti's designs, Brunelleschi immediately left Florence to study in Rome, taking his pupil Donatello with him. He found ancient Roman ruins in bad repair, but analyzed these ancient Roman building techniques in preparation for his ambition for further work on the Cathedral of Florence.

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

Florence

Cathedral, begun 1393, exterior view with completed dome

(Photo: Art Across Time 13.04) |

||||||

|

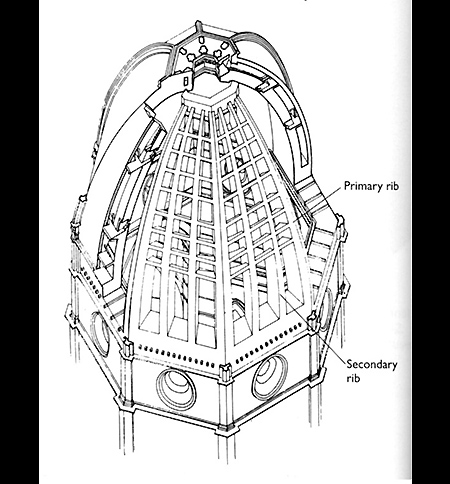

Constructed

in 1393, the Cathedral of Florence still remained without a dome

to cover its 150 foot wide crossing of the nave/choir and transept.

Medieval houses still stood within the area of unfinished construction.

A conference of architects proposed many methods of building a dome

over this open space, such as plaster, wood, stone models, but no

proposal fulfilled the engineering specifications that would hold

up. Brunelleschi came to this conference with a riddle: "How

could one balance and egg on it end ?" The other architects

puzzled and tried, but none could do it, until Brunelleschi demonstrated

his solution by pushing the egg down, breaking it on its narrower

end. -- They were disgruntled, but he then showed them his

|

||||||

| Brunelleschi was hired to build this dome, but Ghiberti, because of his political influence in Florence, was hired as co-engineer with the same pay, despite his lack of architectural skill. Finally, exasperated by the bureaucracy of this arrangement, Brunelleschi finally feigned illness and stayed home, telling the managers that Ghiberti would easily finish the project, until Ghiberti was removed from the work, and Brunelleschi took full charge. | ||||||

|

||||||

|

Lorenzo

Ghiberti "The Meeting of Solomon and Sheba"

1450-52

east door of Florence Baptistery (with perspective lines) gilt bronze relief (Photo: Art Across Time 13.10) |

||||||

| Gentile da Fabriano (c.1370-1427) 13.27 “Adoration of the Magi” altarpiece 1423 Gentile was the exponent of the International Gothic Style in |

||||||

|

||||||

|

Gentile

da Fabiano “Adoration

of the Magi”

80""h x 111" w Uffizi, Florence (Photo: Art Across Time 13.27) |

||||||

| Fra Angelico (c.1387-1455) Fra Giovanni da Fiesole was a Dominican friar, also a friend of Saint Antoninus and knew the popes Eugenius IV and Nicholas V. He was a member of the Order of Preachers and used his art for didactic purposes, rather than a mystical purpose, starting to paint around the age of 28. His style is simple and direct, and used a largeness of form previously used by Giotto and Masaccio, |

||||||

| Paolo Uccello 1396/7-1475 13.40 “Sir John Hawkwood” Paolo Uccello loved to paint birds and other animals, and in his studio had a greatmany studies of birds, so that he was eventually dubbed “Paolo of the Birds” as in Italian “uccello” means birds. and the project was then completed. |

||||||

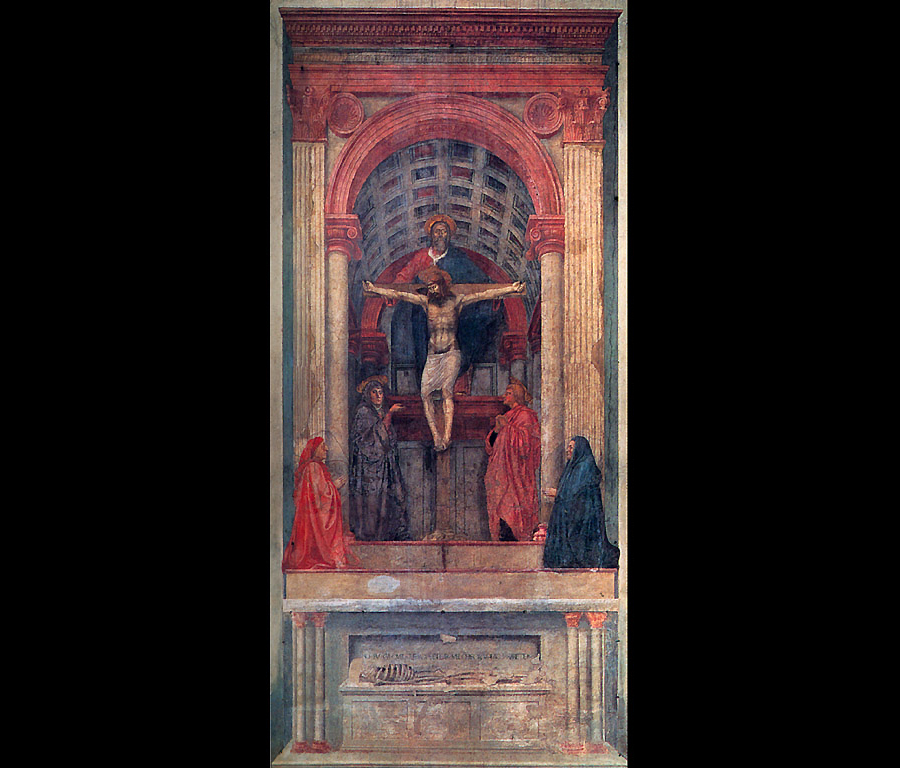

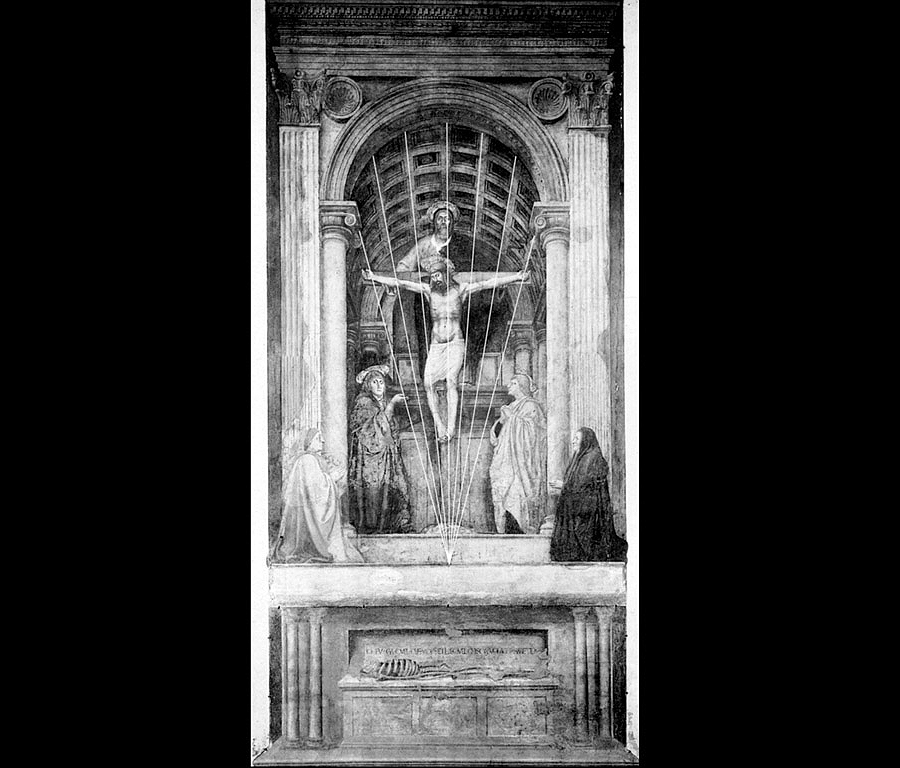

13.24 “The Expulsion from Masaccio was the first great painter of the Italian Renaissance, whose innovations in the use of scientific perspective inaugurated the modern era in painting. |

||||||

|

||||||

|

Masaccio

“The Holy Trinity”

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

Masaccio

“The Holy Trinity”

|

||||||

|

Leon

Alberti 1404-1472 On Architecture published after his death -- based on the writings of the Roman analytical architect Vitruvius. |

||||||

|

Theme of David and Goliath 13.29

Donatello - David, 1430-40, bronze 5' 2" Biblical theme of the graceful David's defeat of the giant Canaan bully Goliath preoccupied Italian artists throughout the Renaissance. David was a symbol of Florence, and its resistance to powerful external forces, papal and foreign armies already for hundreds of years. Monumentality versus Spirituality in 15th century painting: Fra Angelico, Piero della Francesca, Filippo Lippi |

||||||

| Piero

della Francesca (1410/20-1492)

13.13 “Flagellation” (perspective example) 13.45 “Battista Sforza / Federico de Montefeltro” portraits 13.52 “The Dream of Constantine” Piero della Francesca was the most popular painter of the 1400s, due to the mathematical perfection of his forms, and his superb sense of interval. These forms give a serene and timeless quality to his paintings – increased by his soft and pale colors. To modern viewers, there is a sense of Cubism in his forms, and a strong development of symmetry. |

||||||

| Andrea

Mantegna (1431-1506) |

||||||

The Parnassus is a painting by the Italian Renaissance painter Andrea Mantegna, executed in 1497. It is housed in the Musée du Louvre of Paris. The Parnassus was the first picture painted by Mantegna for Isabella d'Este's studiolo (cabinet) in the Ducal Palace of Mantua. The shipping of the paint used by Mantegna for the work is documented in 1497; there is also a letter to Isabella (who was at Ferrara) informing her that once back she would find the work completed. The theme was suggested by the court poet Paride da Ceresara. After Mantegna's death in 1506, the work was partially repainted to update it to the oil technique which had become predominant. The intervention was due perhaps to Lorenzo Leonbruno, and regarded the heads of the Muses, of Apollo, Venus and the landscape. Together with the other paintings in the studiolo, it was gifted by Duke Charles I of Mantua to Cardinal Richelieu in 1627, entering the royal collections with Louis XIV of France. Later it became part of the Louvre Museum. The traditional interpretation of the work is based on a late 15th century poem by Battista Fiera, which identified it as a representation of Mount Parnassus, culminating in the allegory of Isabella as Venus and Francesco II Gonzaga as Mars.The two gods are shown on a natural arch of rocks in front a symbolic bed; in the background the vegetation has many fruits in the right part (the male one) and only one in the left (female) part, symbolizing the fecundation. The posture of Venus derives from the ancient sculpture. They are accompanied by Anteros (the heavenly love), opposed to the carnal one. The latter is still holding the arch, and has a blowpipe which aims at the genitals of Vulcan, Venus' husband, portrayed in his workshop in a grotto. Behind him is the grape, perhaps a symbol of the drunk's intemperance. In a clearing under the arch is Apollo playing a zither. Nine Muses are dancing, in an allegory of universal harmony. According to ancient mythology, her chant could generate earthquakes and other catastrophes, symbolized by the crumbling mountains in the upper left. Such disasters could be cared by Pegasus' hoof: the horse indeed appears in the right foreground. The touch of his hoof could also generate the spring which fed the falls of Mount Helicon, which can be seen in the background. The Muses danced traditionally in wood of this mount, and thus the traditional naming of Mount Parnassus is wrong.Near Pegasus is Mercury, dressing his traditional winged hat, the caduceus (stick with twisted snakes) and the messenger shoes. His presence is due to his role as a protector of the two adulterous. |

||||||

|

||||||

|

Andrea

Mantegna “Parnassus"

Musee du Louvre, Paris (Photo: Art Across Time 13.55) |

||||||

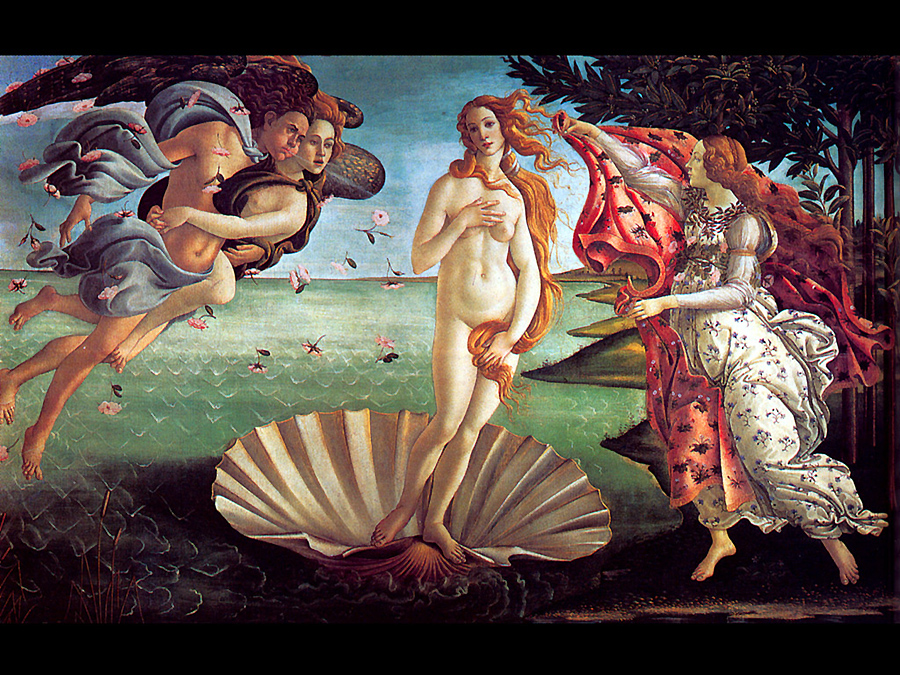

| Sandro

Botticelli (1445-1510) 13.59 “Mystical Nativity” 1500 Botticelli was the most individual and possibly the most influential painter in |

||||||

|

||||||

|

Sandro

Botticelli “Mars

and Venus"

National Gallery, Washington, DC (Photo: Art Across Time 13.56) |

||||||

|

||||||

|

Sandro

Botticelli “Birth

opf Venus"

Galeria degli Uffizi, Florence (Photo: Art Across Time 13.57) |

||||||

| Leonardo

da Vinci (1452-1529) 14.15 “Madonna and Child with St. Anne” (abstract background of mountains) |

||||||

| Giorgine

da Castelfranco (1476/78-1510)

A Venetian painter, a pupil of Giovanni Bellinni, who along with Leonardo was one of the founders of modern painting. He was the first exponent of the small picture in oils. Many of his contemporaries were unable to interpret the subject of Giorgione’s painting “The Tempest,” and analysts today are still mystified. This painting appears to be the first “landscape of mood,” expressing the heat and tension of an approaching thunderstorm. |

||||||

|

||||||

|

Giorgione

Castelfranco “The Tempest"

Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice (Photo: Art Across Time 14.47) |

||||||